The Knowledge Series is a project dedicated to sharing information with our communities on how housing discrimination manifests today. Throughout this week, we will share a series of posts that delve into the history of housing discrimination and what it looks like in our everyday.

You can find Part 1 of the Series here.

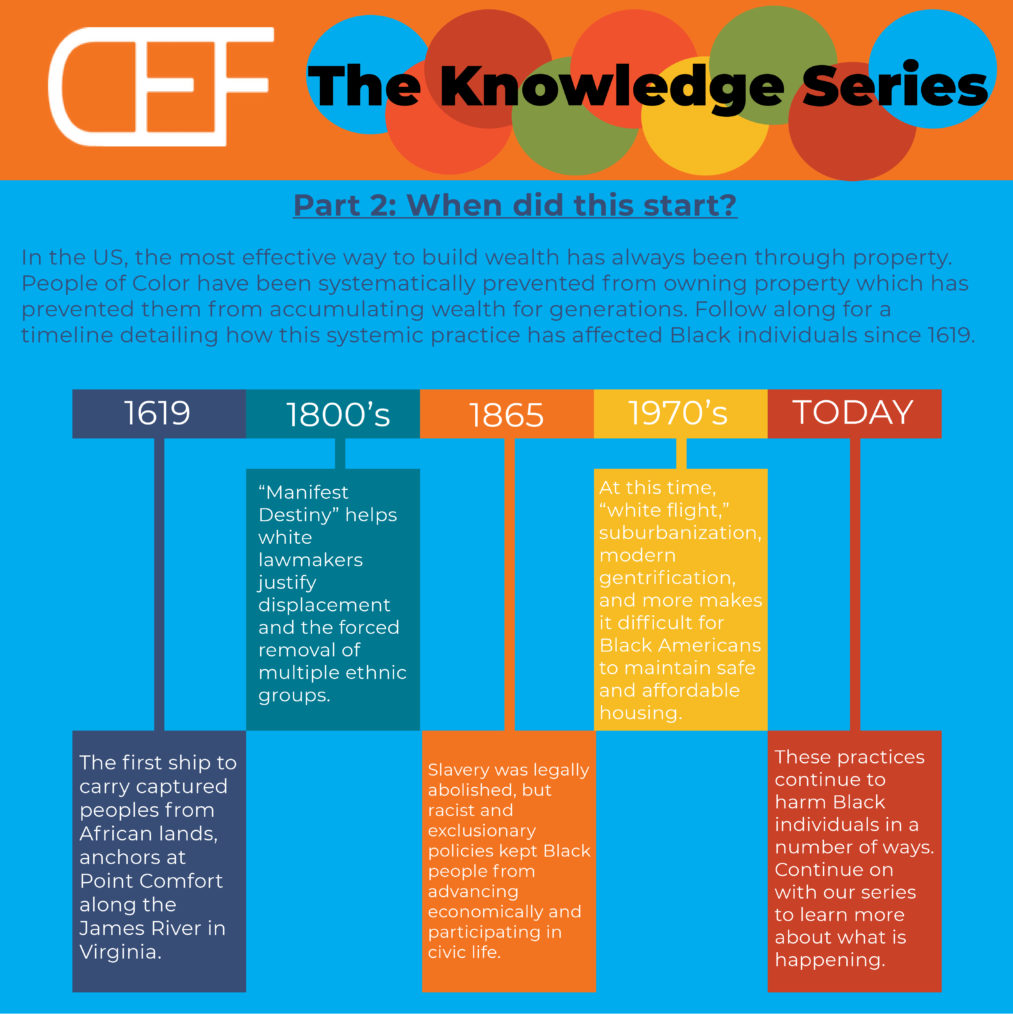

Part 2: When did this start?

In this post, we hope to illustrate a more detailed picture of the birth of American racism, and how its powerful influence has shaped both historical and modern American institutions. The United States has never been “the land of the free” – the enslavement of Africans, as well as Indigenous people, was common practice in this country from its beginnings.

In late August of 1619, the first ship carrying captured peoples from African lands anchored at Point Comfort along the James River in Virginia. These seized individuals were sold into slavery and the practice of enslaving captured Africans quietly grew through custom, rather than by law, throughout the American colonies. By the 18th century, slavery was widespread throughout the Southeast and much of the Northeast. When the majority of the Northeastern United States outlawed the practice of enslaving people in 1804, the divide between the American North and South only furthered. The North came to view slavery as the morally corrupt institution it was (this did not negate their own everyday racism), creating tension with southern states, who relied on free enslaved labor to maintain their economy.

The conditions that enslaved Africans and African Americans were subject to were despicable. As they crossed the Middle Passage, captured Africans were bound by chains on top of one another, sitting in their own urine and feces for days without being fed. Once in America, many enslaved people killed themselves and their families to escape slavery. It speaks volumes that many enslaved people chose to die, or were willing to die, to escape the conditions of their lives. Black people who were enslaved were brutalized by plantation owners, they worked nearly all day, and were kept in dingy and broken housing units. Many chose to make the tumultuous journey to escape enslavement by fleeing northward during the 19th Century. But, this did not always lead to freedom.

Fast forward through the Civil War, which was about the institution of American slavery (specifically, the South’s “right” to maintain their economy, that needed enslaved labor to survive). While slavery was legally abolished in the U.S. in 1865, the South maintained inherently racist and exclusionary policies that kept Black people from both advancing economically and participating in civic life. Jim Crow Laws, voter registration policies, and internalized racism led to continued economic discrimination and physical, verbal, and emotional violence towards Black people at the hands of white* people.

Black people in the U.S., though legally “free,” were still confined and unable to have the same freedoms as whites. Directly following the Civil War, Black men were often only able to find work as sharecroppers, renting plots of land in exchange for a portion of their crops and revenue. Free Black men were often treated unfairly and conned out of resources and profits. Black people were also prevented from participating in public education, creating big discrepancies in literacy and understanding math–greatly impacting their ability to find employment outside of manual labor and their ability to understand finances. Additionally, Black people were prevented from buying their own land due to white supremacist laws and explicitly racist and exclusionary wealth-building policies. These discriminatory practices made it almost impossible for Black families to accumulate wealth at the same levels as white families. And, for those who were successful at building wealth (many, many Black families were very successful at building wealth despite all of the racist laws and people trying to hold them back), there were countless setbacks–including having money and property literally stolen, beatings, fires, and murder (For specific examples, please visit these sites: Freedmen’s Savings and Trust Company, Tulsa Race Massacre, Dismantling Hayti in Durham).

Throughout the 1970s and into the 21st century, practices like “white flight” and gentrification made it difficult for Black families to access safe and affordable housing and effectively attempted to bar Black people from building wealth in the same ways as their white counterparts, through land and property ownership. Property ownership, as well as free labor, have always been the quickest ways to accumulate wealth in the capitalist system which the U.S. subscribes to.

Having assets that can be leveraged increases access to capital and makes it easier to continue to accumulate assets. Imagine one person being able to do this for 400 years, while another can’t. What would be the difference in their wealth accumulation? In 2017, the Survey of Consumer Finances released data showing that the difference in median wealth between Black and white families was striking, $17,600 compared to $171,000–meaning Black families’ median net worth is about 10% of white families (Dettling et al., 2017).

When we consider this history, along with the disproportionate stats we discussed in Part 1 of The Knowledge Series, we begin to see how historical systems manifest in modern-day. Policies and practices in the late 19th and 20th centuries made it extremely difficult for Black families to build and accrue wealth and have led to racial housing discrimination and segregation today. Come back tomorrow to learn more about racialized housing discrimination and why the primary residence ownership for Black families is 28% lower than white families (Dettling et al., 2017).

*In general, CEF uses APA grammar rules in our writing. The APA says that the names of race and ethnic identities should be capitalized, as they are proper nouns. For this series, and moving forward, CEF is intentionally leaving “white” (when referring to a racial identity) lower-cased. We recognize that by capitalizing words we are giving them power and we do not want to encourage white power in any way. Unlike the AP’s explanation for why they are choosing to lower-case “white” we want to be clear that we believe white people do have a shared experience–that is one of privilege. We also believe that undoing racism is the responsibility of white people and worry that implying that white people do not have a shared experience (as the AP does) is a dangerous tactic that is aimed at discounting the responsibility that white people have in undoing racism and white supremacist culture. Ultimately, we know that race is a construct but that racial differences are not. They are real and need to be addressed directly. For any questions or clarifications around CEF’s choice of words please contact ari rosenberg (arir[at]communityef.org).

Dettling, L., Hsu, J., Jacobs, L., Moore, K. & Thompson, J. (2017, September 27). Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. The Federal Reserve. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/recent-trends-in-wealth-holding-by-race-and-ethnicity-evidence-from-the-survey-of-consumer-finances-20170927.htm

No comments yet.