As CEF has grown and blossomed over the years, we have been reminded, time and again, of the importance of being nimble and adaptive as we grow. As you will see in this report, 2020 was no different. In the enclosed stories you will learn how CEF responded to COVID-19 through articles and reflections from CEF’s staff. The report also shares more information about our quantitative impact and our year-end financials. This report is dedicated to the CEF Members who moved on in 2020, we hope you will hold them in your hearts and minds as you read.

Archive | Housing

Time + Talents Podcast: All Things Housing

CEF is excited to share the first episode of the Time + Talents podcast. In this episode, CEF Advocates Lily Levin and Lizzy Kramer interview a number of people involved in housing in Durham County to help listeners learn more about how the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting people’s housing situations and what services are available for people who may need support.

This podcast was arranged by Durham Office & Community Organizer Rosa Green.

We hope you enjoy the podcast. Please share with your networks.

Time + Talents is CEF’s member-driven advocacy platform in Durham. Members chose the theme of this podcast and will continue to be involved in choosing future themes to ensure that the podcast is relevant to their needs and interests.

The Knowledge Series

The Knowledge Series is a project dedicated to sharing information with our communities on how housing discrimination manifests today. Throughout this week, we will share a series of posts that delve into the history of housing discrimination and what it looks like in our everyday.

Please read our previous posts: Part 1, Part 2, & Part 3.

Part 4: Why do these systems continue to exist?

Systemic housing discrimination is still present in modern-day. While it is illegal to discriminate against someone based on race, Black families are still negatively impacted by discriminatory practices, both past and present. When discriminatory practices are used, ending those practices is not enough for people to experience equity–reparations must be made to repair the harms that have been caused. Since the United States has not participated in reparations for Black families, they are still experiencing extreme disparities, especially in housing and financial security.

We’ve discussed in previous posts that Black people make up 51% of the homeless population in Orange County, while only making up 12% of the general population. American slavery and systemic racism, backed by Jim Crow laws, set Black communities back hundreds of years in their attempts to accumulate wealth and assets. Laws throughout the South mandated racial segregation in almost all public facets and denied Black people basic civil, economic, and social rights, including the right to vote. This continued through the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s (and some would say still continues today), making the idea of property ownership and asset accrual for Black families nearly unattainable (“Jim Crow Era,” 2020).

These historical elements, as well as more modern practices such as redlining, white* flight, and gentrification, have had a substantial impact in our own backyard. The wealth that Black communities were able to generate in places like Durham, was systematically taken from them throughout the 20th century through such practices. Additionally, the Northside District of Chapel Hill has been heavily gentrified by UNC students in search of off-campus housing.

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was built by enslaved Black people who were exploited for their labor. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Black employees of the university were funneled to the Northside District because it was one of the least proximate areas to campus at the time (DeWulf, 2017). Northside has been a predominantly Black neighborhood for 175 years, but it is now experiencing gentrification as UNC students seek affordable off-campus housing.

Off-campus living has become increasingly popular for college students in Chapel Hill (with 50% of UNC students currently living off-campus). Many students moved to the Northside District specifically for its relatively affordable rental prices. Furthermore, as the university has grown in geographic size, the Northside District is now comparatively closer to campus than many other off-campus housing options (Cheek, 2017). Nearby Carrboro, also being heavily gentrified, has many high-quality restaurants, thrift stores, and boutiques that add additional appeal for college students. The interest in off-campus housing has driven up rent prices throughout the Chapel Hill-Carrboro community, as landlords see no issue with charging college students above-market rents and has pushed Black residents out of the Northside, a reduction of 60% between 1980 and 2010 (DeWulf, 2017).

As Northside becomes more and more “desirable,” middle-class families have also moved into the area. This further isolates longterm residents of the Northside District from their own community. Since white families moving into neighborhoods like Northside make, on average, two times what Black families make, they are more likely to take advantage of low property costs in historically Black neighborhoods in order to buy homes (Badger et al., 2019). Many of these families renovate their new homes, increasing property values, which leads to increased taxes for entire neighborhoods (Badger et al., 2019). As other middle-class families (typically white) see families that look like them and nice-looking houses they are more likely to purchases homes in the same neighborhood, further gentrifying the area.

Durham, as we discussed yesterday, has also been deeply impacted by housing discrimination. Specifically, the impact of redlining on Black communities in Durham has led to long-lasting disparities for Black neighborhoods. In the 1950s-70s, a phenomenon known as white flight occurred throughout the U.S. This was a process of white people moving out of urban areas, particularly those with significant Black and Brown populations, and into suburban areas, in an attempt to distance themselves from communities of color. White flight causes areas to suffer economically from reduced tax income (due to population losses) and also contributes to harsh policies (Semuels, 2015).

In recent years, Durham’s downtown has also been impacted by gentrification as it has become host to many luxury stores, critically-acclaimed restaurants, and crafty boutiques. When businesses like these move into an area they make it difficult for residents who have lived there for decades to keep up with the rapidly increasing cost of living. The practice of gentrification throughout Chapel Hill, Durham, and the rest of the Triangle, has made housing inequality and segregation even worse (DeMarco and Hunt, 2018).

Black people in the United States face racism every day, but it is often overlooked that racism is deeply ingrained in the housing search process. Things like credit checks, background checks, reference letters, and requiring multiple months of rent upfront disproportionately and negatively affect Black people in their housing search. When you throw in systemic barriers and racist practices, like redlining and gentrification, it imposes a greater hardship on low-income and communities of color. Discriminatory housing practices like redlining and gentrification may not seem racist at face value, but hopefully, the posts in this Series have provided some context to the deeply systemic racial barriers that have plagued Black families in their goals of financial independence and housing security for hundreds of years.

Join us tomorrow for some insight into the work CEF is currently doing and to hear why our mission is so important. CEF is actively working to provide resources to Members experiencing homelessness and/or financial hardship and to dismantle oppressive policies and practices that create a cyclical experience of poverty and housing insecurity for Black people and other people of color. This advocacy work, along with continued education among Staff and Advocates, helps us provide the best support for people experiencing homelessness and financial insecurity in Orange and Durham counties.

*In general, CEF uses APA grammar rules in our writing. The APA says that the names of race and ethnic identities should be capitalized, as they are proper nouns. For this series, and moving forward, CEF is intentionally leaving “white” (when referring to a racial identity) lower-cased. We recognize that by capitalizing words we are giving them power and we do not want to encourage white power in any way. Unlike the AP’s explanation for why they are choosing to lower-case “white” we want to be clear that we believe white people do have a shared experience–that is one of privilege. We also believe that undoing racism is the responsibility of white people and worry that implying that white people do not have a shared experience (as the AP does) is a dangerous tactic that is aimed at discounting the responsibility that white people have in undoing racism and white supremacist culture. Ultimately, we know that race is a construct but that racial differences are not. They are real and need to be addressed directly. For any questions or clarifications around CEF’s choice of words please contact ari rosenberg (arir[at]communityef.org).

Badger, E., Bui, Q., & Gebeloff, R. (2019, April 27). The Neighborhood is Mostly Black. The Homebuyers Are Mostly White. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/04/27/upshot/diversity-housing-maps-raleigh-gentrification.html?searchResultPosition=1

Cheek, S. (2017, April 6). Competition for housing helps drive Chapel Hill rent up to highest in state. The Daily Tar Heel. https://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2017/04/increase-in-chapel-hill-rent-prices-driven-by-competition-for-housing

De Marco, A., & Hunt, H. (2018). Racial Inequality, Poverty and Gentrification in Durham, North Carolina. North Carolina Poverty Research Fund. https://fpg.unc.edu/sites/fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/reports-and-policy-briefs/durham_final_web.pdf

DeWulf, S. (2017, March 2). Saving Northside, the largest black community in Chapel Hill. Omnibus. http://mejo457.web.unc.edu/2017/03/saving-northside-the-largest-black-community-in-chapel-hill/

Jim Crow Era. A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States. (2020, July 28). Georgetown Law Library. https://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/c.php?g=592919&p=4172697

Semuels, A. (2015, July 30). White Flight Never Ended. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/07/white-flight-alive-and-well/399980/

The Knowledge Series

The Knowledge Series is a project dedicated to sharing information with our communities on how housing discrimination manifests today. Throughout this week, we will share a series of posts that delve into the history of housing discrimination and what it looks like in our everyday.

Please read Parts 1 and 2 of the Series.

Part 3: Where does this manifest today?

In our last blog post, we briefly discussed the historical roots of American racism, white supremacy, and how it relates to the current wealth gap between white* and Black families. In this post, we’ll discuss the relationship between racism, white supremacy, and housing inequality in the U.S. today.

In the 1930s, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) began rating communities based on economic and housing factors. These rankings were used to determine eligibility for mortgages, dictating who could and could not buy property in these neighborhoods. The effects of these ratings were astronomical, as poor communities (often primarily composed of Black families) were generally given poorer rankings, families in these neighborhoods were unable to obtain mortgages to purchase homes. The rankings from the HOLC have had long-lasting impacts. Today, almost 64% of communities rated “Hazardous” by the HOLC, remain largely composed of people of color (Mitchell & Franco, 2018). Furthermore, these communities are still experiencing the impacts of the economic discrimination that ensued following the HOLC’s racist community rankings. 85.82% of neighborhoods ranked “Best” by the HOLC are still majority white (Mitchell & Franco, 2018).

These rankings have had lasting impacts. In Durham, for example, between 2007-2014 almost four times more trees were planted in “Best” neighborhoods compared to “Hazardous” neighborhoods (De Marco & Hunt, 2018). In addition to providing beauty, trees increase residential property values and are often a sign of better-maintained neighborhoods.

| The More You Know: The HOLC’s Hold Hits Close to Home A Durham Case Study Literature Review: Racial Inequality, Poverty and Gentrification in Durham, North Carolina Allison De Marco & Heather Hunt, Summer 2018 |

| The practice of redlining was defined by the HOLC’s rankings of largely-Black communities as “less safe” and therefore having a “lower lending ability.” These communities were rated as “Hazardous,” considered the riskiest for lenders, and colored red on maps. Although the HOLC outwardly described their ratings as based in economics, they intentionally redlined historically Black communities to prevent investment in those communities. The HOLC said that the rankings were to determine “creditworthiness using a range of criteria, including race, immigration status, and class.” In Durham, the redlined neighborhoods most closely corresponded with Black, rather than poor, neighborhoods, indicating that not all factors were weighed evenly. At the time, Durham had a thriving Black business community and not all of the redlined communities were poor. Regardless, they were still redlined by the HOLC’s rankings, written off as the least desirable communities to invest in. This made it immediately difficult for families to either move out of or invest in these communities, as their address was commonly a deal-breaker in applying for loans and mortgages. The HOLC effectively worked to dismantle the successful economic systems that Black residents had miraculously built for themselves in Durham. Redlining stifled economic development and doomed communities to a cycle of poverty and racial housing segregation. Though Black Durhamites had created ways to build wealth and obtain land and homes, these communities were then stripped of the wealth-building opportunities they had diligently curated for themselves. Several redlined neighborhoods in Durham are still in a cycle of poverty, as residents are unable to accrue the wealth necessary to move or invest in the community. Although the HOLC is no longer in use, the negative effects are still being felt by Black families today. |

De Marco, A., & Hunt, H. (2018). Racial Inequality, Poverty and Gentrification in Durham, North Carolina. North Carolina Poverty Research Fund. https://fpg.unc.edu/sites/fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/reports-and-policy-briefs/durham_final_web.pdf

Eventually, even heavily segregated urban neighborhoods became undesirable for many white families. Instead, white families chose to leave cities and move to areas on the outskirts of major metropolitan areas, known as suburbs. This process, known as “white flight” or suburbanization, led to an incredible amount of divestment from cities–affecting everything from schools to infrastructure. Black families often lacked the resources needed to move to the suburbs, forcing them to remain in communities that could no longer support their basic needs. This made home and land ownership even more difficult to obtain as banks did not want to invest in dwindling cities.

Soon, the suburbs got old for white families too. Upon moving back into cities, white families decided to aesthetically beautify them by putting in lavish patisseries, designer boutiques, fancy restaurants, and new, more expensive apartment buildings. This is the modern process of gentrification and has further increased housing disparities between Black and white communities. Many Black families cannot always afford the increased property values and, therefore, increased taxes associated with gentrification and are forced to sell their homes because they can no longer afford to stay in their neighborhood.

Durham and Chapel Hill have been so heavily gentrified by white, middle-class college students and families, that the homelessness rate has grown over the past 5 years, despite direct efforts to lower the rate. Tomorrow we will dive into how these systems directly manifest in Orange County and Durham. We will work to better understand how redlining, white flight, and gentrification have taken hold in modern communities and how Black families have been disproportionately affected.

*In general, CEF uses APA grammar rules in our writing. The APA says that the names of race and ethnic identities should be capitalized, as they are proper nouns. For this series, and moving forward, CEF is intentionally leaving “white” (when referring to a racial identity) lower-cased. We recognize that by capitalizing words we are giving them power and we do not want to encourage white power in any way. Unlike the AP’s explanation for why they are choosing to lower-case “white” we want to be clear that we believe white people do have a shared experience–that is one of privilege. We also believe that undoing racism is the responsibility of white people and worry that implying that white people do not have a shared experience (as the AP does) is a dangerous tactic that is aimed at discounting the responsibility that white people have in undoing racism and white supremacist culture. Ultimately, we know that race is a construct but that racial differences are not. They are real and need to be addressed directly. For any questions or clarifications around CEF’s choice of words please contact ari rosenberg (arir[at]communityef.org).

De Marco, A., & Hunt, H. (2018). Racial Inequality, Poverty and Gentrification in Durham, North Carolina. North Carolina Poverty Research Fund. https://fpg.unc.edu/sites/fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/reports-and-policy-briefs/durham_final_web.pdf

Mitchell, B., & Franco, J. (2018, March 20). HOLC “Redlining” Maps: The Persistent Structure Of Segregation And Economic Inequality. National Community Reinvestment Coalition. https://ncrc.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2018/02/NCRC-Research-HOLC-10.pdf

The Knowledge Series

The Knowledge Series is a project dedicated to sharing information with our communities on how housing discrimination manifests today. Throughout this week, we will share a series of posts that delve into the history of housing discrimination and what it looks like in our everyday.

You can find Part 1 of the Series here.

Part 2: When did this start?

In this post, we hope to illustrate a more detailed picture of the birth of American racism, and how its powerful influence has shaped both historical and modern American institutions. The United States has never been “the land of the free” – the enslavement of Africans, as well as Indigenous people, was common practice in this country from its beginnings.

In late August of 1619, the first ship carrying captured peoples from African lands anchored at Point Comfort along the James River in Virginia. These seized individuals were sold into slavery and the practice of enslaving captured Africans quietly grew through custom, rather than by law, throughout the American colonies. By the 18th century, slavery was widespread throughout the Southeast and much of the Northeast. When the majority of the Northeastern United States outlawed the practice of enslaving people in 1804, the divide between the American North and South only furthered. The North came to view slavery as the morally corrupt institution it was (this did not negate their own everyday racism), creating tension with southern states, who relied on free enslaved labor to maintain their economy.

The conditions that enslaved Africans and African Americans were subject to were despicable. As they crossed the Middle Passage, captured Africans were bound by chains on top of one another, sitting in their own urine and feces for days without being fed. Once in America, many enslaved people killed themselves and their families to escape slavery. It speaks volumes that many enslaved people chose to die, or were willing to die, to escape the conditions of their lives. Black people who were enslaved were brutalized by plantation owners, they worked nearly all day, and were kept in dingy and broken housing units. Many chose to make the tumultuous journey to escape enslavement by fleeing northward during the 19th Century. But, this did not always lead to freedom.

Fast forward through the Civil War, which was about the institution of American slavery (specifically, the South’s “right” to maintain their economy, that needed enslaved labor to survive). While slavery was legally abolished in the U.S. in 1865, the South maintained inherently racist and exclusionary policies that kept Black people from both advancing economically and participating in civic life. Jim Crow Laws, voter registration policies, and internalized racism led to continued economic discrimination and physical, verbal, and emotional violence towards Black people at the hands of white* people.

Black people in the U.S., though legally “free,” were still confined and unable to have the same freedoms as whites. Directly following the Civil War, Black men were often only able to find work as sharecroppers, renting plots of land in exchange for a portion of their crops and revenue. Free Black men were often treated unfairly and conned out of resources and profits. Black people were also prevented from participating in public education, creating big discrepancies in literacy and understanding math–greatly impacting their ability to find employment outside of manual labor and their ability to understand finances. Additionally, Black people were prevented from buying their own land due to white supremacist laws and explicitly racist and exclusionary wealth-building policies. These discriminatory practices made it almost impossible for Black families to accumulate wealth at the same levels as white families. And, for those who were successful at building wealth (many, many Black families were very successful at building wealth despite all of the racist laws and people trying to hold them back), there were countless setbacks–including having money and property literally stolen, beatings, fires, and murder (For specific examples, please visit these sites: Freedmen’s Savings and Trust Company, Tulsa Race Massacre, Dismantling Hayti in Durham).

Throughout the 1970s and into the 21st century, practices like “white flight” and gentrification made it difficult for Black families to access safe and affordable housing and effectively attempted to bar Black people from building wealth in the same ways as their white counterparts, through land and property ownership. Property ownership, as well as free labor, have always been the quickest ways to accumulate wealth in the capitalist system which the U.S. subscribes to.

Having assets that can be leveraged increases access to capital and makes it easier to continue to accumulate assets. Imagine one person being able to do this for 400 years, while another can’t. What would be the difference in their wealth accumulation? In 2017, the Survey of Consumer Finances released data showing that the difference in median wealth between Black and white families was striking, $17,600 compared to $171,000–meaning Black families’ median net worth is about 10% of white families (Dettling et al., 2017).

When we consider this history, along with the disproportionate stats we discussed in Part 1 of The Knowledge Series, we begin to see how historical systems manifest in modern-day. Policies and practices in the late 19th and 20th centuries made it extremely difficult for Black families to build and accrue wealth and have led to racial housing discrimination and segregation today. Come back tomorrow to learn more about racialized housing discrimination and why the primary residence ownership for Black families is 28% lower than white families (Dettling et al., 2017).

*In general, CEF uses APA grammar rules in our writing. The APA says that the names of race and ethnic identities should be capitalized, as they are proper nouns. For this series, and moving forward, CEF is intentionally leaving “white” (when referring to a racial identity) lower-cased. We recognize that by capitalizing words we are giving them power and we do not want to encourage white power in any way. Unlike the AP’s explanation for why they are choosing to lower-case “white” we want to be clear that we believe white people do have a shared experience–that is one of privilege. We also believe that undoing racism is the responsibility of white people and worry that implying that white people do not have a shared experience (as the AP does) is a dangerous tactic that is aimed at discounting the responsibility that white people have in undoing racism and white supremacist culture. Ultimately, we know that race is a construct but that racial differences are not. They are real and need to be addressed directly. For any questions or clarifications around CEF’s choice of words please contact ari rosenberg (arir[at]communityef.org).

Dettling, L., Hsu, J., Jacobs, L., Moore, K. & Thompson, J. (2017, September 27). Recent Trends in Wealth-Holding by Race and Ethnicity: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. The Federal Reserve. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/recent-trends-in-wealth-holding-by-race-and-ethnicity-evidence-from-the-survey-of-consumer-finances-20170927.htm

The Knowledge Series

The Knowledge Series is a project dedicated to sharing information with our communities on how housing discrimination manifests today. Throughout this week, we will share a series of posts that delve into the history of housing discrimination and what it looks like in our everyday.

Part 1: Who is affected by homelessness?

Every year in the U.S., communities receiving funding from the McKinney-Vento Act (a U.S. policy that provides federal funds for homeless shelters and other homelessness programs) are required to hold a Point-in-Time (PIT) count in the last week of January to tally all sheltered and unsheltered individuals experiencing homelessness in their area. Data from the most recent PIT counts show there are a projected 9,268 people experiencing homelessness throughout North Carolina. In 2019, the PIT count in Orange County revealed that 131 individuals experienced homelessness on any given night. In the City of Durham, the PIT count revealed 338 individuals experienced homelessness every day in the city.

These numbers are disheartening because at CEF we believe that housing and financial security are human rights. Unfortunately, these rights have not been previously available for many Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC). Today, Black folx are still discriminated against in the housing and employment processes at greater numbers than any other racial group. In taking a deeper look at PIT count data, the numbers show us explicitly that Black people in the U.S. face racial and systemic barriers to obtaining housing and financial security.

Of the 131 individuals experiencing homelessness in Orange County, 51% are Black, despite making up only 12% of the population. Of the 338 homeless in Durham, 78.6% are Black, while making up only 37% of the population. These outrageously disproportionate percentages of homelessness for Black residents of Orange County and the City of Durham are a clear example of the systemic racism which has historically and explicitly barred Black families from accruing wealth through property ownership. The systems which discriminate against Black folx still have a significant impact on communities today, because of the generational trauma garnered through slavery, the Jim Crow South, and the still ever-present institutional racism which is inevitable in a society whose institutions were founded by and for white* men, and only white men.

Come back tomorrow for a blog post diving more deeply into these historical policies and systems which have created modern-day disparities which we must address. We will discuss the historical impacts of slavery and the further, blatant discrimination that Black people in the U.S. faced at the hands of Jim Crow laws in the South. Flowing into modern 20th and 21st century American history, we will use these historical structures to analyze and understand how these systems still create vast disparities for Black folx in the housing and financial sectors.

*In general, CEF uses APA grammar rules in our writing. The APA says that the names of race and ethnic identities should be capitalized, as they are proper nouns. For this series, and moving forward, CEF is intentionally leaving “white” (when referring to a racial identity) lower-cased. We recognize that by capitalizing words we are giving them power and we do not want to encourage white power in any way. Unlike the AP’s explanation for why they are choosing to lower-case “white” we want to be clear that we believe white people do have a shared experience–that is one of privilege. We also believe that undoing racism is the responsibility of white people and worry that implying that white people do not have a shared experience (as the AP does) is a dangerous tactic that is aimed at discounting the responsibility that white people have in undoing racism and white supremacist culture. Ultimately, we know that race is a construct but that racial differences are not. They are real and need to be addressed directly. For any questions or clarifications around CEF’s choice of words please contact ari rosenberg (arir[at]communityef.org).

NC Coalition to End Homelessness. (2019, May). 2019 Homelessness in North Carolina. https://www.ncceh.org/media/files/files/7bd752c5/2019-nc-pit-infographic.pdf

Root, Corey. (2019, April ). Homelessness in Orange County. Orange County Partnership to End Homelessness. https://www.ocpehnc.com/point-in-time-count-data

2019 Annual Report: We Grow Together

As CEF has grown and blossomed over the years, we have been reminded, time and again, of the importance of being nimble and adaptive as we grow. As you will see in this report, 2019 was no different. In the enclosed stories you will learn more about CEF’s deepening advocacy work; read about the programs we’ve built and strengthened; hear directly from Members, Advocates, and Staff about their connection to CEF; and see our quantitative impact.

“I love it, I do”

“I gave a sharp interview, I believe that’s what put me in there,” Leonard says with a smile. In April, he interviewed for one of the newly-completed PeeWee Homes, tiny homes built on the property of Episcopal Church of the Advocate in Chapel Hill. A couple of days later, he received a call: “‘You have one of the PeeWee Homes!’ I went and picked my key up, signed my lease, and been there ever since. This month it’ll be 8 months. I love it, I do.”

After experiencing more than 30 years of homelessness, Leonard’s home still feels new. When Leonard isn’t out working one of his two jobs, his home provides a peaceful haven. He regularly checks on his neighbor, PeeWee (after whom PeeWee Homes is named), who loves to fish in the pond out back. On Sundays, he attends church next door at Episcopal Church of the Advocate.

Before finding his own home, Leonard stayed at the InterFaith Council (IFC) shelter for seven years. There, he heard about and connected with CEF, and began working with Advocates to achieve a comprehensive slate of goals: securing multiple jobs, navigating benefits like food stamps, budgeting, saving for a laptop, and obtaining health insurance.

Leonard’s Advocate, Keely, recalls looking through housing listings for months on end without finding any answers. “Where do we go from here?” she wondered.

One day in the CEF office, Keely heard the PeeWee Homes were becoming available and realized they were an ideal fit: they were located by a bus stop, affordable, and Leonard met the income eligibility guidelines. Several meetings, emails, phone calls, a written application, and one “sharp interview” later, Leonard showed up to his regular Wednesday meeting with good news. “What did they say?” “I got one!” Keely’s notes from their meeting that day say it all, “it was just a billion exclamation points!”

“I was falling down until I started working with CEF. Keely, Zoe, and other Advocates… I’ve basically dealt with all the Advocates here.” Leonard continues to meet with his Advocates on Wednesday mornings, working towards even greater savings and financial goals. “I don’t bother my money in my CEF Safe Savings Account. I let it stay there.”

Originally from Raleigh, Leonard left home when he was 19 or 20. “I’ve been pretty much homeless most of my life. It was a rough life, I didn’t ever think I was going to get back on my feet, but I did. I kept the faith and kept going at it.”

“[Now] I’m on my feet, got me two jobs working two stores. I got my own place. I can look over my shoulder. I’ve got too much to lose now and I’m trying to stay ahead, keep the faith, and keep doing what I gotta do.’”

To help support this work, please consider making a donation during CEF’s Holiday Campaign! Thanks to a generous group of CEF donors who came together to match year-end contributions, your gift to CEF will be doubled through December 31st, up to $38,000!

Heartfelt thanks to our friends at PeeWee Homes, who built Leonard’s home! Learn more about the initiative here: https://peeweehomes.org/

Annual Report 2018 : “it takes a collective”

“We are overwhelmingly grateful for the opportunity to grow with the over 1,000 Members and 250 Advocates who show up every day to care for each other. It encourages us to learn from and lean on one another as we move forward together. Thank you for believing in this community of boundless support as we grow towards the abundant possibilities we have before us.”

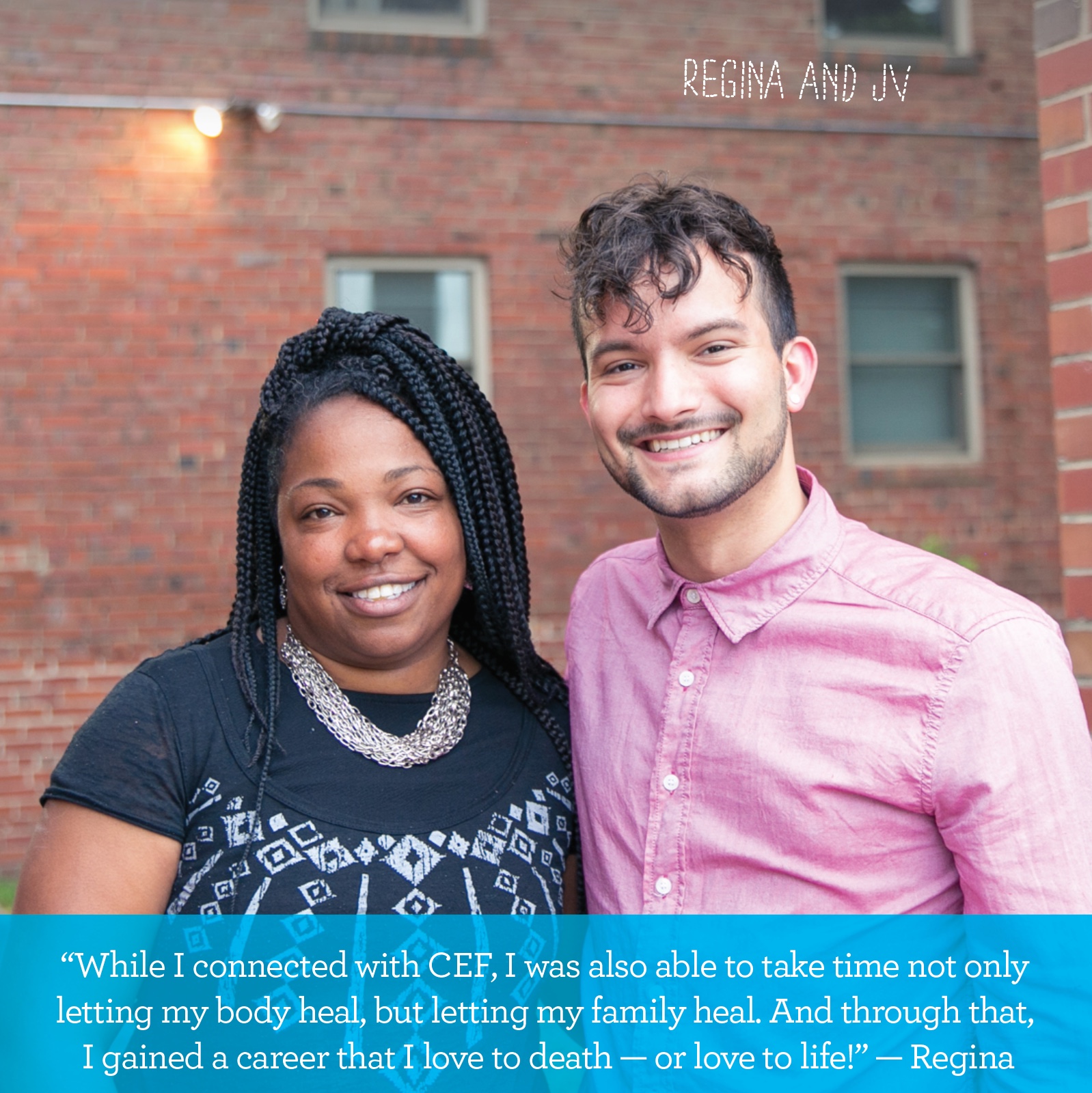

Meet Regina

Regina and her four kids’ lives changed rapidly with the onset of company layoffs, a serious illness, divorce, and loss of their home. Previously, she had built a stable career in military and corporate life. “Don’t ever think that you can’t ever be sitting in the bottom,” she shares.

Regina first met JV, her CEF Advocate, while she was saying at Families Moving Forward, an emergency shelter for families in Durham. Each meeting, she worked on new goals, from building savings and credit to pursuing housing stability and professional growth. “While I connected with CEF, I was also able to take time not only letting my body heal, but letting my family heal. And through that, I gained a career that I love to death — or love to life!”

Now, 1.5 years after joining CEF, Regina has rebuilt a professional life that is driven by passion. After earning certifications in wellness and recovery, she is now an independent recovery coach. She regularly connects her clients with CEF. “I’m a huge advocate! It’s like family … [And] a good connection for whatever you want to grow and be in life.”

Having found stability, Regina is finding ways to weave her success with that of her community’s, by creating job opportunities and leading community change. She founded a successful cleaning business that is dedicated to hiring single parents and people with conviction histories and substance abuse histories. “We’re fighting the same fight,” she shares of the company’s 4 employees.

She also serves on the Board of Recovery Communities of Durham, volunteers as a youth mentor, and advocates for mental health policy and equitable wages. “It’s good to be a part of that change.”